When four children entered the foster care system over 20 years ago, questions arose about what would happen to them. They needed appropriate caretakers. So Julie Jones, then working with Child Protective Services (CPS), broke through barriers in order to fight for the family.

“I was bound and determined to keep them together,” Jones said.

With time and effort, Jones was able to see the siblings adopted together.

“That case probably had the most impact on me because I had to stand up and be their advocate more than I ever had before,” Jones said.

Jones lingered on the word “advocate.” For her, that word means everything about child welfare.

“In my world of working with families and children, there is no greater label for me than being an advocate for kids,” Jones said, “It means permanency for them in so many ways. Are they going to stay with their birth family? Are they going to a relative? Are they going to be adopted?”

Jones still gets emotional talking about that case because she remembers how hard she had to fight.

Now, Jones is the manager of the WKU Lifeskills Center for Child Welfare Education and Research. This center encompasses every avenue of the child welfare workforce with its many agencies, professions and disciplines, Jones said in an interview with the Herald on May 16 at South Campus, where the center is now based.

“I think it’s a misconception that only people with a social work degree work in child welfare,” Jones said.

Child welfare extends to many areas outside of state workers. School social workers, child advocacy centers, doctors and lawyers can all find themselves in child welfare work, Jones emphasized.

“When I was a front-line worker in CPS, I was really surprised at all the different professionals that I worked with,” Jones said. “I worked with a speech pathologist for a long time because they taught one of my kids a basic reflex that he was not born with.”

The goal of her center, Jones says, is to support all of the professionals, individuals and front-line workers in child welfare.

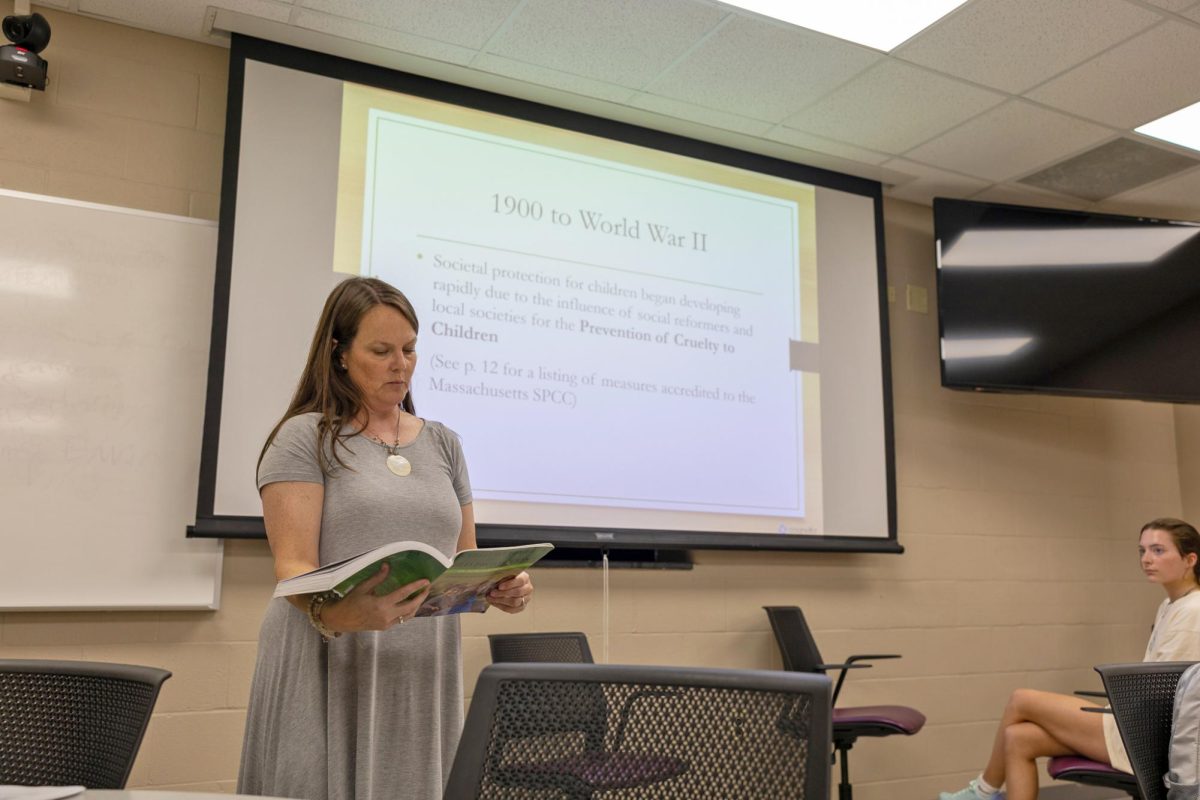

In efforts to share the broadness that child welfare has, WKU’s College of Health and Human Services and Jones’ center created a class in 2022 that meets the Explorations: Social & Behavioral Colonnade requirement: CHHS 100: Introduction to Child Welfare, which is taught by Jones.

“In social work, there’s a program called ‘Child Welfare Prep’ for students that want to go work for the state, but for other students across campus, they might not have the opportunity to learn about what entails child welfare,” Jones said.

The course goes through every detail of child welfare, and Jones invites guest speakers from various professions so that students learn all the different aspects of child welfare.

“The majority of our students have been nursing majors, which makes sense because they’re going to encounter a child, eventually, that has a suspicious bruise,” Jones said.

Jones said that she feels the class is an unbiased and impactful look into the world of child welfare.

Through this class, Jones also said she wants to emphasize that child welfare is an amazing profession to work in.

Jones initially graduated from WKU with a psychology undergraduate degree in 1991. After graduation, she worked at Rivendell Behavioral Health Hospital in Bowling Green for about a year. After leaving the hospital, she moved into retail management for a few years before she decided to find a path to use her degree.

So, she applied to the state as a front-line child protection worker with the Division of Protection and Permanency.

“When I started in child protection, I don’t know that I realized what I would be doing and the impact I would make on families and at the same time, the impact they would make on me,” Jones said.

Kentucky Youth Advocates, an organization that advocates for policies that give children greater opportunities, summarized most recent data from the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ 2022 report. According to their summary, Kentucky now ranks 14th in the nation in child victims of maltreatment.

“While there has been a 48% reduction in child victims of maltreatment from 2018 to 2022,” Kentucky Youth Advocates said, “Kentucky is around 60% higher than the national rate (7.7 per 1,000) of child maltreatment at 12.3 per 1,000 children.”

Jones, with her 19 years of experience, shares the continual need for child welfare workers. She shows students her own stories, putting faces on the statistics.

When remembering the four children that eventually got adopted, Jones says that case still drives her because it had a very happy ending.

“That’s what we want for kids that have experienced trauma and have been in [the] child welfare system,” Jones said, “a happy ending.”

News reporter Cameron Shaw can be reached at [email protected].

This post was originally published on 3rd party site mentioned in the title of this page